Abstract

Stimulation of the immune system by pathogens, allergens, or autoantigens leads to differentiation of CD4+ T cells with pro- or anti-inflammatory effector cell functions. Based on functional properties and expression of characteristic cytokines and transcription factors, effector CD4+ T cells have been grouped mainly into Th1, Th2, Th17, and regulatory T (Treg) cells. At least some of these T cell subsets remain responsive to external cues and acquire properties of other subsets, raising the hope that this functional plasticity might be exploited for therapeutic purposes. In this study, we used an Ag-specific adoptive transfer model and determined whether in vitro-polarized or ex vivo-isolated Th1, Th17, or Treg cells can be converted into IL-4–expressing Th2 cells in vivo by infection of mice with the gastrointestinal helminth Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. Th1 and Th17 cells could be repolarized to acquire the expression of IL-4 and lose the expression of their characteristic cytokines IFN-γ and IL-17A, respectively. In contrast, both in vitro-generated and ex vivo-isolated Treg cells were largely resistant to repolarization. The helminth-induced conversion of Th1 or Th17 cells into Th2 cells may partially explain the inverse correlation between helminth infection and protection against autoimmune disorders.

CD4+ Th cells constitute a major part of the adaptive immune system and orchestrate protective immunity against pathogens. Naive CD4+ T cells circulate through peripheral lymphoid tissues where they can recognize Ags in the form of peptide/MHC class II complexes on APCs. They acquire distinct effector or regulatory cell fates depending on the local environment, the quantity of Ag, and the quality of the APCs. Differentiation is mainly driven by cytokines, which induce expression of lineage-specific master transcription factors (1). The effector cell fate is subsequently conserved in part by cytokine- and transcription factor-mediated feedback regulation and epigenetic modification of histones and DNA (2).

Th1 cells secrete IFN-γ and protect against intracellular pathogens, but they also cause autoimmune inflammation. Their development is mediated by IL-12 and IFN-γ, which induce expression of the master transcription factor T-bet (3, 4). Th2 cells produce IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, orchestrate inflammation during allergic dis-orders, and contribute to protective immunity against helminths. The Th2-associated transcription factor GATA-3 appears essential for initiation of the Th2 cell fate and is induced by IL-4 and IL-2 (5, 6). Th17 cells represent a more recently identified T cell subset characterized by expression of the transcription factor RORγt and the cytokines IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 (7, 8). Th17 cells play a proinflammatory role during autoimmune responses and also protect against various fungal and bacterial infections. The cytokines secreted by these three effector T cell subsets support their own development and suppress the development of the other two cell fates, thereby leading to an early and efficient polarization of a developing immune response (9). All three effector T cell types can be suppressed by naturally occurring regulatory T (nTreg) cells or inducible (de novo-induced) Treg (iTreg) cells that express the forkhead transcriptional repressor Foxp3 and constitute a separate lineage of Th cells (10).

The initial concept that each Th cell subset represents a terminal state of differentiation or stable cell lineage has been revised since several reports clearly demonstrated that some Th subsets, especially iTreg and Th17 cells, can be induced to express signature cytokines of other subsets (reviewed in Refs. 11, 12). Th17 cells can be converted into Th1 cells that express T-bet and IFN-γ (13–17). In vitro-generated murine Th2 cells or ex vivo-isolated human and murine memory Th2 cells could be repolarized to obtain an IL-4 plus IFN-γ or IL-4 plus IL-17 double-producing status (18–21). The induction of T-bet and IFN-γ expression in repolarized Th2 cells is dependent on combined signaling by IFNs and IL-12 (22). Whether nTreg cells possess functional plasticity remains a matter of debate. It has been shown that adoptive transfer of genetically marked nTreg cells into lymphopenic hosts can result in conversion into follicular helper T cells cells or pathogenic IL-17– or IFN-γ–expressing T cells (23–26). However, an inducible fate mapping approach demonstrated that nTreg cells have a stable phenotype and do not convert into other effector cell subsets in vivo (27).

To our knowledge, conversion of isolated Ag-specific Th1, Th17, or Treg cells into Th2 cells in vivo has not been described. Furthermore, most results are based on in vitro studies with defined cytokine cocktails. Although in vitro studies can help to elucidate major differentiation pathways, they cannot provide an environment that faithfully represents the complex environment found in vivo. Therefore, a direct comparison of the plasticity of in vitro-generated or ex vivo-isolated effector T cells is required to get a better understanding about the functional plasticity of Th cells and develop new therapeutic approaches for chronic inflammatory or autoimmune disorders. Future therapies could be based on Ag-specific reprogramming of pathogenic Th1 or Th17 cells into Th2 or Treg cells with anti-inflammatory properties. Therefore, we performed adoptive transfer experiments with ex vivo-isolated and in vivo-generated Th1, Th17, or Treg cells and determined their potential to convert into Th2 cells in vivo after restimulation during infection with the gastrointestinal helminth Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. Our results show that Treg cells were largely resistant to Th2 polarization. However, Th1 and Th17 cells could be efficiently reprogrammed to lose their initial cytokine expression profile and acquire the capacity to express IL-4.

Materials and Methods

Mice

IL-4 green fluorescence-enhanced transcript (4get) mice have been described (28) and were provided by R.M. Locksley. These mice carry an IRES-enhanced GFP (eGFP) construct inserted after the stop codon of the Il4 gene and served as IL-4 reporter mice. Depletion of regulatory T cell (DEREG) mice (29) expressing a diphtheria toxin receptor/eGFP fusion protein under the control of the Foxp3 gene locus and IL-4/IL-13–deficient mice (30) have been described. DO11.10 TCR-transgenic mice and BALB/c mice were originally obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (31). DO11.10 mice were further crossed to 4get-CD90.1 and DEREG mice. Animals were housed according to institutional guidelines, used at 6–12 wk age, and were sex matched. All experiments were approved by the local federal government Regierung von Oberbayern.

In vitro generation of OVA-specific effector T cells

Polarizing T cell cultures were setup with pooled total spleen and lymph node cells of DO11.10-4get-CD90.1 or DO11.10-DEREG mice at a density of 2 × 106 cells/ml. Cells were stimulated with 200 ng/ml OVA323–339 peptide (Apara Bioscience, Denzlingen, Germany) and cultivated in RPMI 1640 (PanBiotech, Aidenbach, Germany) or IMDM (PAA Laboratories, Pasching, Austria), both supplemented with 10% FCS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 10 U/ml streptomycin (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany), and 5 × 10−5 M 2-ME (Merck Chemicals, Darmstadt, Germany). To induce Th1 and iTreg differentiation the cultures contained 20 ng/ml recombinant human (rh) IL-2, 5 ng/ml recombinant mouse IL-12 (ImmunoTools, Friesoythe, Germany), and 20 μg/ml anti–IL-4 (clone 11B11; BioXCell, West Lebanon, NH) for Th1 cell development or 20 ng/ml rhIL-2, 15 ng/ml rhTGF-β1 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), 20 μg/ml anti–IL-4, and 20 μg/ml anti–IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2; BioXCell) for iTreg cell development. For Th17 polarization IMDM was further supplemented with 20 ng/ml recombinant mouse IL-6 (PeproTech), 5 ng/ml TGF-β1, 20 μg/ml anti–IL-4, and 20 μg/ml anti–IFN-γ. All cells were cultured for 5 d.

In vivo polarization of OVA-specific Th1 and Th17 cells by modified vaccinia virus Ankara/OVA infection or by intranasal OVA administration

For generation of OVA-specific Th1 cells, DO11.10-4get-CD90.1 mice were infected with 107 PFU modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA), which encodes chicken OVA and results in expansion of OVA-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleen (32). Viable Th1 cells (CD4+KJ1-26+IFN-γ+IL-4eGFP−) from the spleen were identified by IFN-γ staining (IFN-γ secretion assay detection kit; Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) and purified by FACS on day 6 postinfection.

The induction of Th17 differentiation in DO11.10-4get-CD90.1 mice was achieved by a single intranasal administration of OVA protein (500 μg OVA in 50 μl PBS; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Three days later IL-17A production of OVA-specific Th17 cells in the lung was analyzed by an IL-17A secretion assay detection kit (Milteny Biotec). For adoptive transfer experiments CD4+KJ1-26+IL-17A+IL-4eGFP− lung cells were pu-rified by FACS.

Adoptive T cell transfer and induction of repolarization by N. brasiliensis infection and OVA protein administration

Distinct OVA-specific CD4+ T cell subsets were generated in vitro by cell culture or directly isolated ex vivo as mentioned above and purified by FACS (at least 98% purity). Cells were washed twice with PBS, and 5 × 105 in vitro-generated cells or 3–6 × 104 ex vivo-isolated cells were given i.v. into naive recipient BALB/c or IL-4/IL-13–deficient mice in 200 μl PBS. One day after adoptive transfer, mice were infected s.c. with a mixture of third-stage larvae of N. brasiliensis (500 third-stage larvae) and OVA (100 μg; Sigma-Aldrich) in 200 μl 0.9% NaCl. Three days after infection, mice received an intranasal challenge with 500 μg OVA in 50 μl PBS. T cell subset repolarization was analyzed on day 6 postinfection.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

For FACS analysis cell suspensions were prepared from mediastinal lymph nodes (mLNs), spleen, or PBS-perfused lung samples by mechanical disruption using a 70-μm nylon strainer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). After erythrocyte lysis samples were washed in FACS buffer (PBS, 2% FCS, 1 mg/ml NaN3). The following mAbs were used for FACSorting and identification of adoptively transferred CD4+ T cells (all Abs were purchased from eBioscience, San Diego, CA): PerCP-Cy5.5–conjugated anti-CD4 (clone RM4-5), PE-conjugated anti-CD25 (clone PC61.5), PE-conjugated anti-CD44 (clone IM7), allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD90.1 (clone HIS51), and allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-DO11.10 TCR (clone KJ1-26). Samples were acquired on FACSCanto II instru-ments or FACSAria for sorting (BD Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA). Dead cells and cell doublets were discriminated by gating. Data were analyzed by FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Staining of IFN-γ+, IL-17A+, or IL-4+ T cells by secretion assay detection kits

For identification of IFN-γ+–, IL-17A+–, or IL-4+–producing T cells, 4 × 106/ml total cells from mLNs, spleen, or lung were restimulated for 4 h with 2 μg/ml ionomycin and 40 ng/ml PMA (both Sigma-Aldrich) in supplemented IMDM or RPMI 1640 medium. For sorting of in vitro-polarized Th1 cells, restimulation was performed with 200 ng/ml OVA323–339 instead of PMA and ionomycin. After stimulation, cytokine secretion was analyzed with the corresponding cytokine secretion assay detection kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec). In brief, cytokine released from the cell is captured on the cell surface and can be detected directly with a PE-labeled mAb or indirectly with a biotinylated mAb.

Results

Rapid in vivo polarization of Ag-specific Th2 cells from purified naive CD4 T cells

Most peripheral CD4+ T cells displays a naive phenotype and lack the expression of master transcription factors and cytokines that are characteristic for polarized T effector cell populations. This uncommitted state of differentiation confers maximal functional plasticity, which decreases after naive T cells undergo the first steps of effector cell differentiation. To determine the efficiency of Th2 polarization from naive precursors in vivo, we transferred 106 FACS-purified naive T cells from spleen and lymph nodes of OVA-specific TCR-transgenic mice that had been crossed to sensitive IL-4eGFP reporter mice on a CD90.1 congenic background (DO11.10-CD90.1-4get mice) into BALB/c mice (CD90.2). The recipient mice were then infected with a mixture of OVA and the helminth N. brasiliensis followed by intranasal administration of OVA 3 d later. Expansion and Th2 polarization of the donor T cells were de-termined on day 6 postinfection by flow cytometry (Fig. 1A). The N. brasiliensis–OVA infection induced an at least 30-fold expansion of the donor T cells as they constituted a population of 1–2% of total lymphocytes in the lung and mLNs of infected mice, whereas only 0.01–0.05% of donor T cells could be found in these organs in noninfected mice (Fig. 1B). About 50% of the donor T cells acquired a Th2 phenotype indicated by the expression of IL-4eGFP and lack of IFN-γ production (Fig. 1C).

In addition to their strong Th2-polarizing activity, helminths may induce expansion of Foxp3-expressing Treg cells and this phenomenon could at least partially explain their immunosuppressive potential (33, 34). To directly determine whether N. brasiliensis infection leads to de novo induction of Ag-specific Treg cells (iTreg cells), we transferred purified naive T cells (CD44loFoxp3eGFP−) isolated from DO11.10 mice that had been crossed to Foxp3eGFP reporter mice (DEREG mice) into BALB/c recipients followed by N. brasiliensis–OVA infection. Only 0.5 and 2% of the transferred T cells acquired Foxp3eGFP expression in the mLNs and lung, respectively (Fig. 1D).

Taken together, these results demonstrate that N. brasiliensis induces a highly polarized Th2 response. Therefore, we used this infection model to determine whether in vitro- or in vivo-differ-entiated Th1, Th17, or Treg cells can be reprogrammed to acquire a Th2 phenotype in vivo.

Treg cells are largely resistant to Th2 conversion during helminth infection

The potential of Treg cells to acquire other effector T cell fates in vivo remains controversial, and it is unclear whether Foxp3-expressing Treg cells can be converted into IL-4–expressing cells in vivo. To address this question we first generated OVA-specific iTreg cells by in vitro culture with T cells from DO11.10-DEREG mice. CD4+KJ1-26+Foxp3eGFP+ iTreg cells from these cultures were isolated by cell sorting with 99% purity and transferred into BALB/c recipient mice (Fig. 2A). One day after transfer mice were infected with N. brasiliensis–OVA followed by intranasal OVA challenge 3 d later. The expansion of the transferred T cells and the stability of Foxp3 expression in these cells were analyzed by flow cytometry on day 6 postinfection. The expansion of the transferred iTreg cells was comparable to the expansion of transferred naive T cells (compare Fig. 2A and Fig. 1B).

About 60% of the transferred iTreg cells appeared Foxp3eGFP− in lung and mLNs, indicating that they had lost expression of the master transcription factor Foxp3 (Fig. 2A). IL-4 production was observed in 6–8% of these ex-iTreg cells. In contrast, IL-4 expression could be detected in only 1–2% of iTreg cells that remained Foxp3eGFP+, suggesting that loss of Foxp3 expression facilitates conversion of iTreg cells into Th2 cells. However, the capacity for conversion of iTreg cells into Th2 cells appears rather poor when compared with the differentiation of naive T cells into Th2 cells.

Next, we determined whether ex vivo-isolated nTreg cells can be converted to Th2 cells by Ag-specific stimulation in the context of helminth infection. CD4+KJ1-26+Foxp3eGFP+ nTreg cells were directly isolated by sorting from lymph nodes and spleen of DO11.10-DEREG mice, transferred into BALB/c mice followed by N. brasiliensis–OVA infection, and analyzed 6 d later for expression of IL-4 and Foxp3eGFP. Less than 2% of the transferred nTreg cells produced IL-4, and >85% continued to express Foxp3eGFP (Fig. 2B). Collectively, these results indicate that nTreg cells are rather resistant to Th2 polarization in vivo.

Efficient conversion of Th1 cells into Th2 cells

From a therapeutic perspective it seems attractive to induce Ag-specific repolarization of Th1 cells into Th2 cells in vivo and thereby ameliorate chronic Th1-dominated inflammatory diseases. Therefore, we determined whether in vitro- or in vivo-generated Th1 cells could be converted into Th2 cells by N. brasiliensis–OVA infection. OVA-specific Th1 cells were generated in vitro by stimulation of lymphocytes from DO11.10-4get-CD90.1 mice under Th1-polarizing conditions. IFN-γ–secreting Th1 cells were purified by cytokine capture assay and cell sorting (CD4+KJ1-26+IFN-γ+IL-4eGFP−) and directly transferred into BALB/c recipients followed by N. brasiliensis–OVA infection (Fig. 3A). When recipient mice were analyzed 6 d later, ∼40% of the donor cells had lost IFN-γ production and ∼30% of the donor cells acquired an IL-4–expressing phenotype. Interestingly, we observed that the frequency of IL-4–expressing cells was comparable between cells that maintained IFN-γ production and cells that had lost IFN-γ production (Fig. 3A). IL-4 protein secretion could be induced from donor cells in lung and lymph nodes after restimulation (Supplemental Fig. 1).

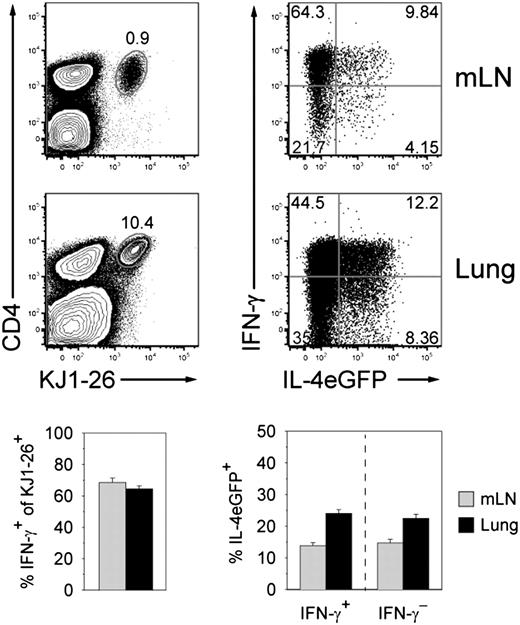

To further investigate the lineage stability of in vivo-generated Th1 cells, we immunized DO11.10-4get mice with a single dose of replication-deficient MVA-encoding OVA to induce differentiation of OVA-specific Th1 cells (Fig. 3B). On day 6 postinfection Th1 cells were isolated from the spleen by IFN-γ capture assay, and 5 × 104 Th1 cells per recipient mouse were transferred followed by N. brasiliensis–OVA infection. When mice were analyzed 6 d later, the transferred cells constituted a small but distinct population in mLNs and lung (Fig. 3C). About 70–80% of these cells had lost the capacity to produce IFN-γ and ∼50% expressed IL-4eGFP. Even higher frequencies of IL-4eGFP–expressing cells (70%) were observed among the remaining IFN-γ+ cells.

We conclude that Th1 effector cells can be efficiently instructed in vivo within a few days to lose their potential to produce IFN-γ and instead acquire the capacity to express IL-4, reflecting their conversion from Th1 to Th2 cells.

Conversion of Th1 cells into Th2 cells occurs in the absence of exogenous IL-4 and IL-13

IL-4 plays an important role for stable differentiation of Th2 cells, and autocrine IL-2 and IL-4 production from T cells can be sufficient for this process (35). To test whether exogenous IL-4 is also dispensable for conversion of Th1 cells into Th2 cells, we transferred in vitro-generated Th1 cells (CD4+KJ1-26+IFN-γ+IL-4eGFP−) into IL-4/IL-13–deficient recipient mice followed by N. brasiliensis–OVA infection (Fig. 4). About 15–25% of the transferred Th1 cells acquired IL-4eGFP expression and a substantial fraction of these cells had lost the capacity to produce IFN-γ. However, the frequencies of partially converted Th1 cells (IFN-γ+IL-4eGFP+) and fully converted Th1 to Th2 cells (IFN-γ−IL-4eGFP+) were reduced by 30% when compared with transfers into wild-type mice. This indicates that exogenous IL-4, which may be provided by T cells or innate cell types such as basophils, mast cells, or eosinophils, enhances the efficiency of repolarization but is not essential for this process.

Functional plasticity of Th17 cells in the context of N. brasiliensis infection

The differentiation state of Th17 cells appears rather flexible when compared with Th1 or Treg cells. In particular, reprogramming of Th17 cells into IFN-γ– or Foxp3-expressing cells has been demonstrated in vitro and in vivo (13, 15, 17). However, it remains unclear whether Th17 cells can be induced to acquire a Th2 phenotype in vivo. Thus, we generated OVA-specific Th17 cells in vitro, purified IL-17A–producing CD4 T cells (CD4+KJ1-26+IL-17A+IL-4eGFP−) by FACS after capture assay, and transferred them into BALB/c mice followed by N. brasiliensis–OVA infection. Samples from mLNs and lungs were analyzed 6 d postinfection by IL-17A capture assay and IL-4eGFP expression (Fig. 5A). Sixty to 80% of the transferred Th17 cells had lost the capacity to secrete IL-17A, and 20–30% acquired IL-4eGFP expression. IL-4 protein secretion could be induced from donor cells in lung and lymph nodes after restimulation (Supplemental Fig. 2). Next, we decided to determine the functional plasticity of in vivo-generated Th17 cells. We observed that intranasal administration of OVA in DO11.10-4get-CD90.1 mice results in efficient induction of Th17 cells within 3 d (Fig. 5B). These cells were purified by IL-17A capture assay and cell sorting (CD4+KJ1-26+IL-17A+IL-4eGFP−) and 5 × 104 cells were transferred into recipient mice. We were unable to find the transferred Th17 cells in the lung, which might be due to the low numbers of transferred cells or impaired recruitment to this tissue under the Th2-polarizing conditions of an N. brasiliensis infection. However, the transferred cells could be detected in the mLNs and >90% of these cells had lost the capacity to secrete IL-17A (Fig. 5B). About 40% of the cells expressed IL-4eGFP, reflecting a complete conversion from Th17 into Th2 cells. These experiments demonstrate that in vitro-generated or ex vivo-isolated Th17 cells are susceptible to repolarization into Th2 cells (Fig. 6).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the functional plasticity of effector and regulatory CD4 T cells in vivo. Using a helminth infection model and adoptive T cell transfers we observed that purified Th1 and Th17 cells can be rapidly and efficiently induced to express IL-4. Both T cell subsets either coexpressed IL-4 together with IFN-γ or IL-17A, respectively, or even lost their initial cytokine profile and converted to IL-4+IFN-γ− or IL-4+IL-17A− cells. This indicates that they completely converted into Th2 cells as defined by expression of IL-4 and lack of characteristic cytokines of other Th cell subsets. To our knowledge the complete conversion of in vivo-generated Th1 or Th17 cells into Th2 cells has not been shown before. In contrast to the apparent flexibility of Th1 and Th17 cells, we found that iTreg or nTreg cells could not be induced to acquire IL-4 expression.

Early experiments by Mosmann and Coffman (36) established the concept that Th1 and Th2 cells are stable and terminally differentiated cell lineages. However, these studies were mainly based on in vitro-generated T cell clones that had been cultured in high concentrations of polarizing cytokines for long periods of time. With the discovery of other T cell subsets, including Treg and Th17 cells, it became apparent that the dualistic view of Th cell differentiation was too simplistic. Furthermore, studies during the past few years have shown that some T cell subsets retain functional plasticity and can be converted into other Th cell subsets (11, 12, 18, 37). Short-term in vitro cultures stimulated under Th1- or Th2-polarizing conditions could be reprogrammed to acquire the opposite phenotype whereas long-term cultures appeared more stable (38). The functional plasticity was drastically reduced after the cells had undergone three to four cell divisions (39). The initial lineage commitment is passed on to daughter cells by sophisticated molecular mechanisms, including feedback and cross-regulation of transcription factors, chromatin remodeling, and epigenetic modifications (1, 12). This process is important for both the efficient formation of a large effector cell population and a pool of memory T cells that provide protective immunity against pathogens. The experimental settings used to repolarize Th cells ranged from in vitro systems to bacterial and viral infection models or autoimmune models, which are known to induce strong Th1 or Th17 responses. Although in vitro experiments have shown that IL-4 expression can be induced in Th1 or Th17 cells, it remains unclear whether this occurs in vivo. The present knowledge on Th cell plasticity is largely based on in vitro experiments with defined culture conditions that only partially reflect the in vivo milieu during an ongoing immune response. It was therefore important to use a physiologic infection model and directly compare the generation of Th2 cells from in vitro- or in vivo-generated Th1 and Th17 cells. In both situations we stimulated DO11.10 TCR-transgenic cells for 3–6 d with specific Ag and sorted effector cells based on their release of IFN-γ or IL-17A. Instead of using cytokine-reporter mice, we decided to use cytokine secretion assays to isolate Th1 and Th17 cells. This had the advantage that we could be sure to isolate cytokine-producing effector cells. Cytokine-reporter mice may not always faithfully report cytokine protein expression due to the genetic manipulations of cytokine genes or differences in mRNA or protein stability of the reporter construct (40). For example, expression of eGFP in IL-4eGFP reporter mice (4get mice) reflects IL-4 transcription and is sufficient to mark Th2 cells, although IL-4 protein expression requires restimulation of the cells and dephosphorylation of the translation initiation factor eukaryotic initiation factor 2-α (41).

The rapid induction of IL-4 expression in Th1 effector cells by N. brasiliensis infection is a remarkable finding. It has been shown that binding of T-bet to the IL-4 promoter and binding of the transcriptional repressor Runx3 to the DNAse I hypersensitive site IV of the il4/il13 locus blocks IL-4 expression in Th1 cells (42). Additionally, T-bet can be phosphorylated by Itk and then inhibit the function of GATA-3, which is required for Th2 cell differentiation (43). Genome-wide analysis of histone methylation marks have shown that the il4/il13 locus in Th1 cells was associated with repressed chromatin indicated by trimethylation of lysine at position 27 of histone 3 (44). Although these molecular mechanisms may help to stabilize the Th1 cell fate, they did not prevent the induction of IL-4 expression during infection with N. brasiliensis. Unfortunately, the cell numbers that could be recovered after in vivo repolarization were too low to perform epigenetic or func-tional analyses.

Interestingly, the conversion of Th1 cells into Th2 cells was only partially dependent on exogenous IL-4, suggesting that this process could be driven by an IL-4–independent pathway that might involve signaling via STAT-5-coupled cytokine receptors that contain the common γ-chain as signaling unit including the receptors for IL-2, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15, and IL-21 (45). Alternatively, conversion could be induced by signaling via the Notch receptor pathway. Binding of Jagged-1 to the Notch receptor results in cleavage and translocation of the Notch intracellular domain to the nucleus where it drives IL-4 expression by binding to the RBP-J element in the 3′ untranslated region of IL-4 and direct induction of GATA-3 expression (46, 47). Future experiments with Notch- or common γ-chain–deficient mice should help to clarify whether these pathways are indeed involved in Th1 to Th2 conversion.

Th17 cells have initially been shown to form a separate lineage of Th effector cells (7, 48). However, recent evidence indicates that the differentiation state of these cells is quite flexible. They can easily convert into Th1 cells, especially under lymphopenic conditions (13–15). Lineage tracing studies have revealed that a substantial fraction of Th17 cells converts to Th1 cells during infection of normal mice with Candida albicans or during the course of experimentally induced autoimmune encephalomyelitis (17). The conversion could be induced by IL-12–mediated activation of STAT-4 and inhibition of RORγt (49). A previous study demonstrated that ex vivo-isolated Th17 cells were more resistant to in vitro repolarization into Th1 and Th2 cells as compared with in vitro-generated Th17 cells (50). However, Lexberg et al. (50) isolated Th17 cells from 6-mo-old untreated DO11.10 mice that spontaneously had ∼3.5% Th17 cells among CD4+CD62L− effector/memory cells. The ontogeny of these Th17 cells remains unclear, and it is quite possible that their differentiation status is less flexible as compared with Th17 cells that were induced in an Ag-specific manner. Additionally, critical factors for Th2 polarization may be missing in the cultures used to repolarize these cells into Th2 cells.

Th2 cells may also retain functional plasticity since it has been shown that they can further differentiate into IL-9–expressing cells under influence of TGF-β (51). An IL-17A+ Th2 population has been observed during infection of mice with N. brasiliensis or induction of allergic inflammation of the lung (21). The expression of IFN-γ could be induced in Th2 cells that were generated in vitro and repolarized by adoptive transfer and infection of mice with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (18). These so-called “Th2+1” cells expressed both GATA-3 and T-bet. The coexpres-sion of IL-4 and IFN-γ has been observed before and these cells were initially termed Th0 cells since it was proposed that they represent a precursor population that has not yet decided whether it should further differentiate into Th1 or Th2 cells (52, 53). In this respect it will be interesting to compare methylation marks of cytokine and transcription factor genes in Th0 generated early during an immune response and Th2+1 cells that result from re-polarization of differentiated Th2 cells. The lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-induced conversion of in vitro-generated Th2 cells resulted in ∼30% IL-4+IFN-γ+ cells. However, most cells (50–60%) were IL-4−IFN-γ+, indicating that they underwent a complete conversion from Th2 into Th1 cells (18). Because large numbers of sorted Th2 cells were transferred and rested in vivo for 30 d before infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, it remains possible that a small population of contaminating uncommitted T cells accounts for the expansion of IL-4−IFN-γ+ cells. Lineage tracing studies with suitable reporter mice might be helpful to exclude this possibility. Using such lineage tracing studies with Foxp3-Cre or IL-17A-Cre knock-in mice have shown that nTreg cells represent a stable lineage whereas Th17 cells can convert to Th1 cells in vivo (17, 27).

In general, memory Th cells seem to be quite flexible (18, 19, 37). Our results indicate that ex vivo-isolated Th1 and Th17 cells can be more efficiently converted to Th2 cells as compared with their in vitro-generated counterparts. It is possible that the high concentrations of polarizing cytokines used for in vitro generation of these cell subsets render the cells more resistant to conversion. Functional plasticity may be related to slowly declining epigenetic modifications or lower expression levels of master transcription factors allowing memory T cells to reset their effector cell program. Zhu and Paul (54) proposed that aged individuals with a decreased pool of naive T cells and a restricted T cell repertoire may benefit from cross-reactivity and functional plasticity of memory T cells. However, T cell responses are usually highly Ag-specific and chances for reactivation by cross-reactivity with pathogens that require a different type of T cell response are very low. It remains unclear whether functional plasticity of effector/memory T cells provides evolutionary benefits.

Nevertheless, the flexibility could be used therapeutically in chronic allergic or autoimmune diseases. Such therapeutic strategies have to be developed with great care to prevent undesired side effects. Parasitic helminths have been shown to ameliorate in-flammatory and autoimmune diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease, type I diabetes, multiple sclerosis, and asthma (reviewed in Refs. 55–57). Anti-helminthic therapy of helminth-infected school children in Gabon caused an increased sensitization against house dust mites (58). A similar inverse correlation has now been shown for multiple sclerosis patients (59). Treatment of Crohn’s disease patients with eggs from Trichuris suis, the whipworm of pigs, improved the disease score (60). The mechanisms used by helminths to suppress the immune system include the induction of inhibitory cytokines such as TGF-β and IL-10 and de novo generation of Treg cells. Based on our present study helminths may also convert existing proinflammatory or autoimmune Th1 and Th17 cells into Th2 cells that induce the differentiation of alternatively activated macrophages by release of IL-4 and IL-13 (61). Alternatively activated macrophages can suppress T cell responses by expression of Fizz-1/Relm-α and PD-L2, a ligand for the inhibitory receptor PD-1 on T cells (62, 63). The molecular mechanisms by which helminths induce Th2 cells are not well understood. Future studies will hopefully lead to identification of helminth-derived factors that promote Th2 polarization and may be used therapeutically to ameliorate Th1/Th17-associated diseases.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to A. Turqueti-Neves and C. Schwartz for helpful discussion and critical reading of the manuscript and A. Bol and W. Mertl for animal husbandry.

Footnotes

This work was supported by German Research Foundation Grants SFB 571 (to D.V.) and SFB 456 (to I.D.).

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

References

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.